Don’t be put off by the title at the top of this seasonal post. We haven’t come over all ‘Bah humbug’ and decided to lecture everybody on the most efficient way to cook their Brussel sprouts (a quick tip though – don’t bother cutting a cross in the base as it’s a process step which doesn’t add any value).

Nor do we want to spoil Christmas by talking about work and ignoring the festivities. Here at Catalyst we love Christmas, but we simply can’t help ourselves looking at a few of our favourite yuletide customs and habits and musing upon how they came to be.

After all, it’s easy to think of Christmas as you’re about to celebrate it this year and imagine that’s the way it’s always been, but, like everything else, the modern Christmas has evolved over the years, with much of the template being set down during the Victorian era and refined during the intervening period. Taking a look at some of these refinements, and considering exactly how Santa manages to cram so much productivity into such a short period of time, we couldn’t help but ponder the effect that innovation, standardisation and improvements in efficiency have had upon what we now take for granted as festive frivolity. Anyone who has to cook a full Christmas dinner for 15 or so relatives will surely agree that a process of trial and error and a refinement of working methods is simply the only way to get things done properly and ensure that the cranberry, turkey and roast potato all hit the plate at exactly the same time.

Take the Christmas cracker, for instance. It may look like the kind of thing which has been around forever, but it was actually invented in 1846 by one Thomas Smith, a baker and confectioner from London. During a visit to Paris he caught sight of sugared almond sweets wrapped in coloured tissue twisted at either end, and decided to import the idea to make his bon-bons more interesting and appealing in the run up to Christmas. In the spirit of innovation, however, he also added a ‘snap’, a strip of paper soaked in chemicals which, when rubbed, reacted to the friction and let out a ‘snap’ noise. This was later refined to include mottoes and poems and, in later years, novelty items. In its early stages, the cracker was sold throughout the year and the motto inside was often topical in nature, but the market came to be focussed upon the festive period.

Here at Catalyst we love a Christmas cracker joke, and amongst the most groan worthy we’ve produced are the following:

[box]‘An optician who is unable to see the value of continuous improvement is probably suffering from Asigmatism’

‘Sick Sigma describes a poor process in the NHS’

‘An optimist sees the glass as half full, the pessimist as half empty. The lean expert just thinks the glass is too big’

‘With all the soot in Victorian chimneys, is it possible that Father Christmas was the first recognised Black Belt?’[/box]

Trust us, around the Catalyst Christmas table, those had us clutching our sides!

The humble Christmas card is another seasonal product which was invented and then popularised through a search for efficiency and standardisation. The card itself was invented in 1843 by Sir Henry Cole, and was driven by his irritation at the amount of seasonal correspondence he had to produce. Rather than write each greeting by hand he decided to have a specific card printed, thus saving himself hours of time and bouts of writer’s cramp. The introduction of lower and standardised postal rates in 1840 encouraged more and more people to indulge in the habit of sending printed cards, and designs which soon became popular included robins, Father Christmas, evergreens and snow covered landscapes.

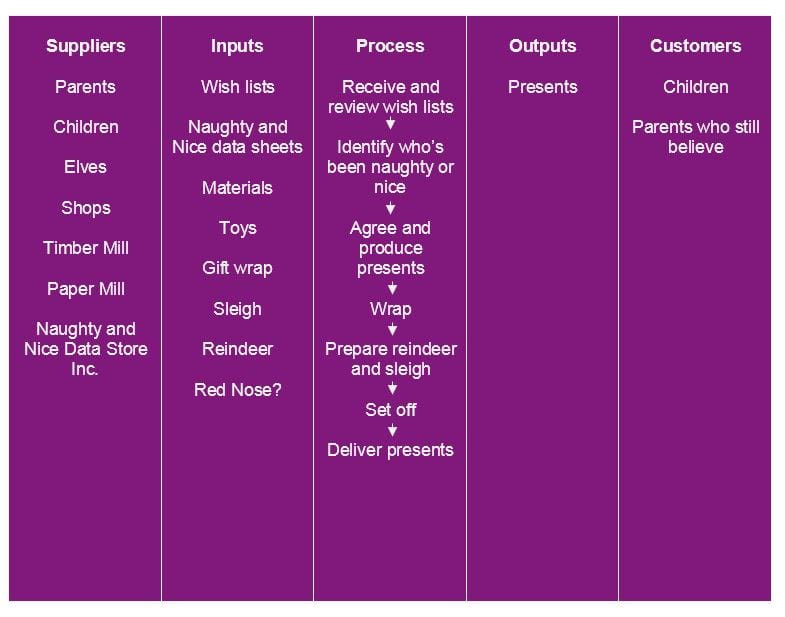

Although these are examples of efficiency driving seasonal innovation which we can all relate to personally, perhaps the most impressive yuletide process is that utilised by Santa himself. Given that he has to deliver gifts to all the good boys and girls on the planet in a single night, it’s perhaps not surprising that Santa and his elves have worked to refine and streamline their processes, ensuring success from the North to the South pole and all points between by developing a SIPOC diagram. The first step taken by Santa is the identification of the start and stop points of the process. In this case, the start of the process occurs when Santa receives and reviews the letters sent by children and their parents and the final step consists of the delivery of the presents.

Santa’s SIPOC diagram

His first step is to receive and review the Christmas letters sent by the children and their parents. The end step will be the delivery of the presents. The development of the diagram is one which works backwards from the point of view of the customers to Santa himself, making it perhaps more of a ‘COPIS’ diagram than SIPOC. The diagram breaks the process of making and delivering Christmas gifts into a set of steps and interested parties. In the column headed Suppliers, Santa will have listed the parents, children, elves, shops, timber mill, paper mill and the Naughty and Nice Data Store Inc.

The Inputs into the process, the next column, include wish lists, date provided by the Naughty and Nice company, toys, gift wrapping paper, sleigh and reindeer (including Rudolf and his red nose). This then leads onto the Process itself, which involves reviewing the wish lists and inputting the Naughty and Nice data, followed by the production of agreed gifts, the wrapping of the gifts, the take-off in the sleigh and the delivery of the gifts down each and every chimney. The Outputs, of course, are the gifts themselves, with the customers being made up of two groups; children and parents who still believe in Santa.

Finally the all important Customer is the millions of children that rely on Santa getting all the other elements in his process right so that they get their presents on Christmas morning.

The aim of the SIPOC diagram, as utilised by Santa, is to take a step back from the process and overview the delivery of outputs without becoming too entangled in the minutiae of operational detail. By creating simple and easily defined parameters, a SIPOC diagram outlines a high level process map, confirming input requirements from suppliers whilst noting, as is the case with Santa, that customers can also be suppliers as well, in this case supplying the letters detailing exactly which gifts are wanted.

Although relatively simple in detail, the diagram is a valuable means of being able to review the major steps included and, where possible, highlight those which are clearly not adding value to the process. It’s fairly typical, in businesses and organisations of all kinds, for only 10-15% of the steps outlined in a SIPOC diagram to actually add value, and the act of setting them out in such a simple and linear fashion is often the first move toward eliminating delays and disconnects.

Of course Santa, being magical, produces the most efficient processes of all, and that includes the steps he decided to take in calculating the most efficient route map when delivering his goodies. We’ve written about the method he used to do so elsewhere, find out more about Santa, spaghetti and bees here.

All that’s left now is for us to say Merry Christmas from everyone at Catalyst.